Glossary

Broadsheet (broadside)

Other languages

- Dutch: plano, prent, plakkaat

- French: placard, broadside (used in French scholarship), feuille volante, estampe (image with text), gravure (image only)

- German: Einblattdruck, Flugblatt

- Italian: stampa, foglio volante, foglio sciolto

- Polish: plano, jednokartkowy druk ulotny

- Spanish: doble folio, hoja impresa por una sola cara

Material form

Single-sheet printSubject

Commerce and administration, Games and humour, Knowledge and skills, Music and performative literature, Narrative literature and history, News and current affairs, Religion and moralityDescription

Broadsheets (or broadsides) is a portmanteau term referring to a form of prints consisting of only a single sheet, printed on one side only in the case of broadsides. Though not directly relatable to specific genres (as there were many genres that existed in both broadsheet format and more elaborate forms), some genres were more or less exclusively printed in the broadsheet format, including penny prints, hornbooks, ordinances and forms. The general terms print/prent/estampe commonly refer to a broadside with a printed image that could be accompanied by a short text or caption.

There were many differences in size and paper quality, as the broadsheets were often used in a wide variety of contexts and purposes, some requiring mass print of a cheaper nature, and some warranting more careful printing techniques. Often, broadsheet pamphlets, proclamations, penny prints, handbills, almanacs or ballads would be used partly as (decorative) wallpaper or posters in public spaces. The Dutch plakkaat and French placard refer to this application on a wall, specifically for public announcements.

Although mostly cheap and easy to spread, not all broadsheets can be classified as ‘popular literature’ per se. Some forms of broadsheets, such as the indulgence, could be highly expensive and thus unaffordable for a larger public. Others, such as academic dissertations for example, were printed exclusively in Latin rather than in the vernacular. McShane (2011, 341-342) distinguishes between commissioned broadsides (mostly by church and secular authorities, e.g. indulgences, proclamations, epitaphs) and retail broadsides (e.g. ballads, hornbooks, sheet-almanacs). Broadside genres relating to news and polemics overlapped these two categories: ‘Commissioned on a not-for-profit basis in order to manipulate political opinion, these items found themselves, whether intentionally or not, on the open market, but often at an uneconomic cost.’

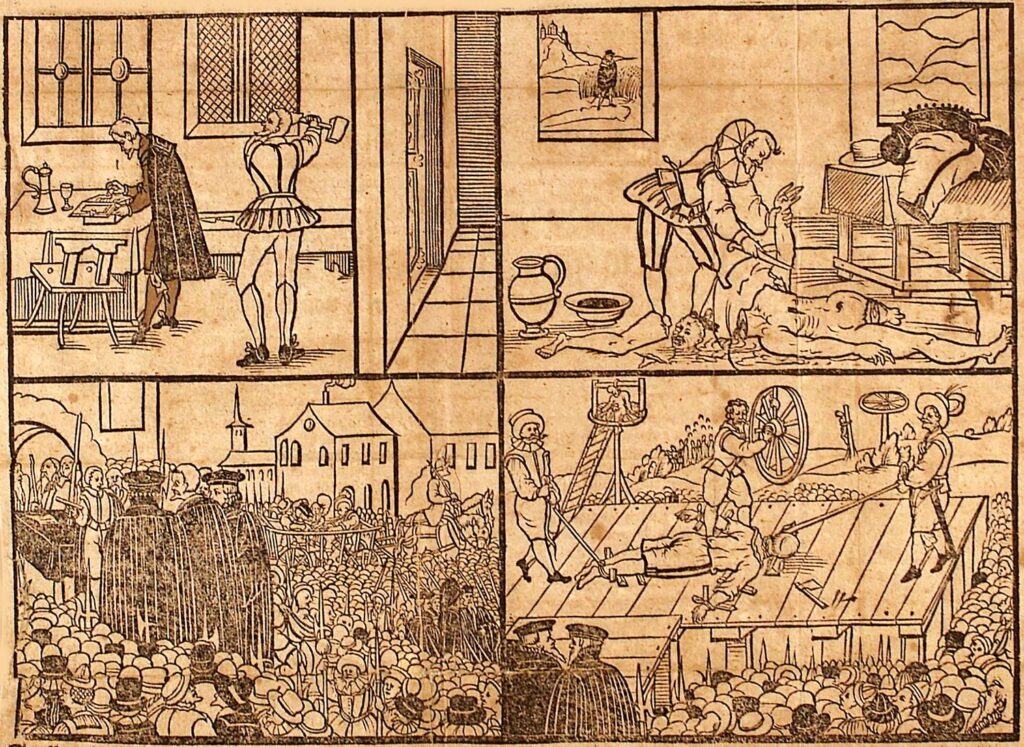

In Italy broadsheets were often used to convey pedagogical and moralising content. These were often illustrated either with a single central image, or towards the end of the 16th century, with a number of small, sequentially placed images which told a story, rather like an early ‘comic strip’ as David Kunzle has termed them (Kunzle 1973). These could be produced in different formats, and whilst some featured more expensive engravings, others employed very sketchy, rudimentary woodcuts that were barely updated over the centuries, destined for a cheaper market.

In Venice (and probably elsewhere) printed recipes which illustrated the dosage and use of remedies had to be distributed together with the remedy/secret on sale, both by apothecaries, by quacks and by the so-called ‘particular people’ (laypeople who applied for licences to produce and sell secrets that had been devised thanks to their ‘diligent study and investigation’). Since 1547 (but probably before) the Venetian Health Office ordained this obligation.

During the plague outbreak in 1576-77 the Venetian Health Office also distributed printed recipes for self-help (see Plague sheet): their texts explained not only the dosage/usage of the remedies but also how to apply them at home. These recipes were intended for self-help and printed in folio format (to be affixed in specific areas of the town) and in quarto format for personal/household reading.

In Spain the term broadsheet does not have one specific equivalent. In bibliographical sources they are encountered as ‘1o’, doble folio, and hoja impresa por una sola cara. Unfortunately, Spanish broadsheets have hardly been preserved. Broadsheets for ecclesiastical administration or religious devotion (such as indulgences, religious poetry and religious images) have survived in relatively great numbers. Also secular, administrative broadsheets such as royal edicts, proclamations and local ordinances take up a large share. Other genres are almanacs, occasional poetry, auques, aleluyas (penny prints) and news broadsheets.

Surprisingly, in France the broadsheet does not appear to be a very prominent category in the early centuries of print. Ordinances were usually produced as a pamphlet. Later, and especially on a local level, administrative and political broadsheets, such as placards, were of greater importance. French penny prints such as the image d’Épinal, for instance, were published in the form of a broadsheet, as were estampes (printed image with a short text, e.g. a poem) and gravures (printed image, either woodcut or engraving).

In German scholarship, Einblattdruck is used for all kinds of single-sheet prints (equivalent to broadsheet) while Flugblatt tends to be used more specifically for occasional prints (single or double-sided), mostly containing sensational news.

Related terms

ballad, criminal narrative, devotional literature, hornbook, martyr story, New Year prints, penny print, plague sheet, playbill, proclamation

Sources

A. Amitrano Savarese and A. Rigoli (eds.), Fuoco, acqua, cielo, terra. Stampe popolari profani della Civica Raccolta Achille Bertarelli (Vigevano: Diakronia, 1995).

D. Bellingradt, ‘Das Flugblatt im Medienverbund der Frühen Neuzeit: Bildtragendes Mediengut und Recycling-Produkt’, Daphnis 48:4 (2020), 516-538.

O. Elyada, Presse populaire et feuilles volantes de la Révolution à Paris, 1789-1792: inventaire méthodique et critique (Paris: Société des études robespierristes, 1991).

A. Fox, The Press and the People: Cheap Print and Society in Scotland, 1500-1785 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), chapter 6: ‘Handbills and Placards’.

D. Gentilcore, Medical Charlatanism in Early Modern Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

W. Harms et al. (ed), Deutsche Illustrierte Flugblätter des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts 7 vols. (Tübingen etc. 1980–2018).

S.F. Matthews Grieco, ‘Pedagogical Prints: Moralizing Broadsheets and Wayward Women in Counter-Reformation Italy’, in: G.A. Johnson and S.F. Matthews Grieco (eds.), Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 61-87.

M. Grillo, Leggi e bandi di antico regime (Cargeghe: Editoriale Documenta, 2014), esp. Chapter 1.

W. Harms, M. Schilling, Das illustrierte Flugblatt der frühen Neuzeit. Traditionen, Wirkungen, Kontexte (Stuttgart: Hirzel, 2008).

D. Kunzle, The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973).

A. McShane, ‘Ballads and Broadsides’, in: J. Raymond (ed.), The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 339-362.

S. Minuzzi, Sul filo dei segreti medicinali. Farmacopea, libri e pratiche terapeutiche a Venezia in età moderna (Milan: Unicopli, 2016), esp. 119-132, 222-227.

P. Needham, The Printer and the Pardoner (Washingon: Library of Congress, 1986).

A. Pettegree (ed.), Broadsheets: Single-Sheet Publishing in the First Age of Print (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2017).

C.L. Preston, M.J. Preston, The Other Print Tradition. Essays on Chapbooks, Broadsides, and Related Ephemera (New York [etc.]: Garland, 1995).

U. Rozzo, La strage ignorata. I fogli volanti a stampa nell’Italia dei secoli XV e XVI (Udine: Forum, 2008).

R. Salzberg, Ephemeral City: Cheap Print and Urban Culture in Renaissance Venice (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014).

M. Schilling, Bildpublizistik der frühen Neuzeit. Aufgaben und Leistungen des illustrierten Flugblatts in Deutschland bis um 1700 (Tübingen 1990).