Glossary

Penny print

Other languages

- Dutch: centsprent, kinderprent, volksprent, schoolprent (19th c.), heilig(je), sankt(je), mannekensblad (Flanders)

- French: imagerie populaire, image d’enfants, image d’Épinal, feuil d’images, planche d’imagerie, saint

- German: Bilderbogen, Neuruppiner

- Italian: incisioni, stampe incise, rami, stampe popolari (modern term)

- Polish: druk straganowy, druk jarmarczny

- Scottish: dabbities

- Spanish: aleluya, auca, auque

- Russian: lubok

- Scandinavia: folkelige grafik

Material form

Single-sheet printSubject

Games and humour, Knowledge and skills, Narrative literature and history, Religion and moralityDescription

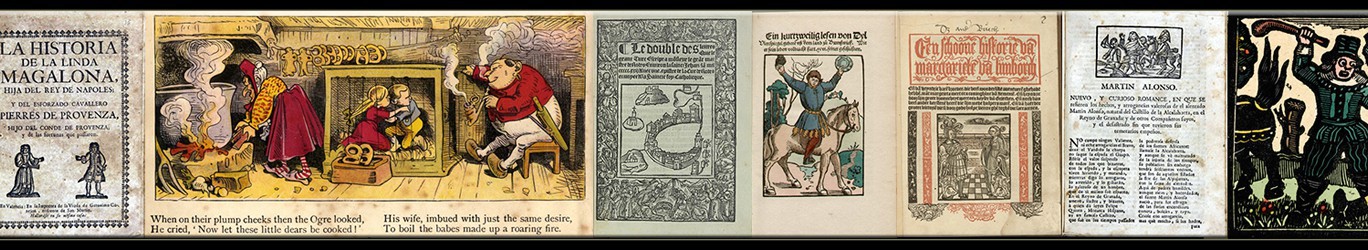

Penny prints are cheap broadsides, printed on one side and illustrated with 8 to 48 woodcuts. Rhyming captions below the images either narrated the story or explained the (non-fictional) pictures. They were sold either in black and white or coloured by hand using two or three simple colours. Sometimes (as in Spain) they were printed on coloured paper. A miscellaneous world of wonders was represented in these prints, running from topography, fashion and natural history to bible stories, lives of saints, historical heroes, allegories, fables and fictional narratives. Penny prints can be found in many European countries, although they made their first appearance and were popular in different periods, were not always equally diverse, and were called different things. In most countries print publishers did not only produce separate titles, but focused on series of penny prints, which were numbered in order to encourage consumers to collect them. The name by which penny prints were known in different language-areas could be related either to their low price, the content, the intended audience, or the place of production.

In the Dutch Republic the ‘Golden Age’ of the penny print was the 18th century, whereas in other European countries a substantial growth occurred in the 19th century. Although the 16th century saw an explosion of one-sided prints with woodcuts, many hesitate to label these prints as ‘folk prints’ or ‘penny prints’ as they were not available to the lowest classes of society. In the Netherlands, from about 1670 we can speak of the large-scale production of penny prints as cheap bulk goods. From that moment on these prints started to address children. The quality of penny prints seems to have decreased over the 18th century as the result of larger scaled production. At the same time, printers of penny prints began to sell bundles of prints, prentenboeken or ‘picture books’. In Spain this happened in the 19th century, with the production transferred from Catalan cities to Madrid. Moreover, in the 19th century printers from Épinal and other French eastern towns, together with the German printers from Neuruppin, consolidated an audience shift, increasingly addressing children. Adopting lithography, they could afford higher print-runs and a more varied design, starting a mass production of paper toys in parallel to more traditional penny prints.

In England they are better known as catchpenny prints. There this genre includes ‘last dying speeches’ or accounts of ‘bloody murders’ sold to those who attended public executions, which are also sometimes referred to as ‘gallows literature’. These ephemeral publications were intended for the lower classes and most sold for a penny or less. They were often compiled in a hurry, with scant regard for veracity or accuracy. Fictitious catchpennies were known as ‘Cocks’.

Related terms

catchpenny print, broadside, history, devotional literature, criminal narrative, children’s book and schoolbook

Sources

J. Auringer, website Bilderbogenforschung, https://www.bilderbogenforschung.de/

A. Amitrano Savarese and A. Rigoli (eds.), Fuoco, acqua, cielo, terra. Stampe popolari profani della Civica Raccolta Achille Bertarelli (Vigevano: Diakronia, 1995).

N. Boerma, A. Borms, A. Thijs, J. Thijssen (eds.), Kinderprenten, volksprenten, centsprenten, schoolprenten. Populaire grafiek in de Nederlanden 1650-1950 (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2014).

J.-F. Botrel, ‘Les ‘aleluyas’ ou le degré zéro de la lecture’, in J. Maurice (ed.), Regards sur le XXe siècle espagnol (Nanterre : Université Paris X-Nanterre, 1995), 9-29.

J. Díaz, ‘Literatura de cordel. Pliegos y aleluyas’, in: J. Ȧlvarez Barrientos (ed.), Se hicieron literatos para ser políticos. Cultura y política en la España de Carlos IV y Fernando VII (Madrid/Cádiz: Biblioteca nueva, 2004), 63-82.

P.S. Falla and S. Lambert, French Popular Imagery: Five Centuries of Prints (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1974).

J. Gardham, ‘Valentines and Dabbities’, blog Glasgow University Library Special Collections Department Book of the Month, February 2002, https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/feb2002.html

J. Gomis and J. Salman, ‘Tall Tales for a Mass Audience. Dutch Penny Prints and Spanish Aleluyas in Comparative Perspective’, Quaerendo 51 (2021), 95-122.

Th. Gretton, Murders and Morality: English Catchpenny Prints, 1800-1860 (London: British Museum Publications, 1980).

E. Hilscher, Die Bilderbogen im 19. Jahrhundert (Munich: Verlag Dokumentation, 1977).

D. Kunzle, The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973).

J. Mistler et al., Épinal et l’imagerie populaire (Paris: Hachette, 1961).

S. O’Connell, The Popular Print in England (London: British Museum, 1999).

J. Salman, ‘An Early Modern Mass Medium: The Adventures of Cartouche in Dutch Penny Prints (1700-1900)’, Cultural History 7 (2018), 20-47.

J. Salman, ‘Devotional and Demonic Narratives in Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century Dutch Penny Prints’, in: D. Atkinson and S. Roud (eds.), Cheap Print and the People: European Perspectives on Popular Literature (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019), 121-138.

T. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).