Glossary

Ballad

Other languages

- Danish: skillingstrykk

- Dutch: straatlied, ballade, liedblad, liedboek

- Finnish: Arkkiveisut

- French: chanson, cantique populaire, recueil de chansons, chansonnier, vaudeville, parolier

- German: Ballade, Lied, Bänkelsang

- Italian: ballata, cantare, canzone, capitolo, frottola, lamento, laude

- Norwegian: skillingstrykk

- Polish: pieśń, śpiewnik (song book)

- Spanish: pliego suelto poético, romance, copla, trova, trovo, trobo, troba, glosa, seguidilla, paso (pasillo), canción, cancionero (song book), villancico

- Swedish: skillingtryck

Material form

Printed book, Single-sheet printSubject

Music and performative literature, Narrative literature and history, News and current affairs, Religion and moralityDescription

A ballad was a popular song that had many subgenres such as the love ballad, the satirical ballad and the execution ballad. Ballads were common across Europe. They covered multiple themes, such as heroic tales, love stories, criminal stories, news items and political songs related to contemporary events. In their broadsheet form, which was particularly common in Britain, they appeared in roughly two categories.

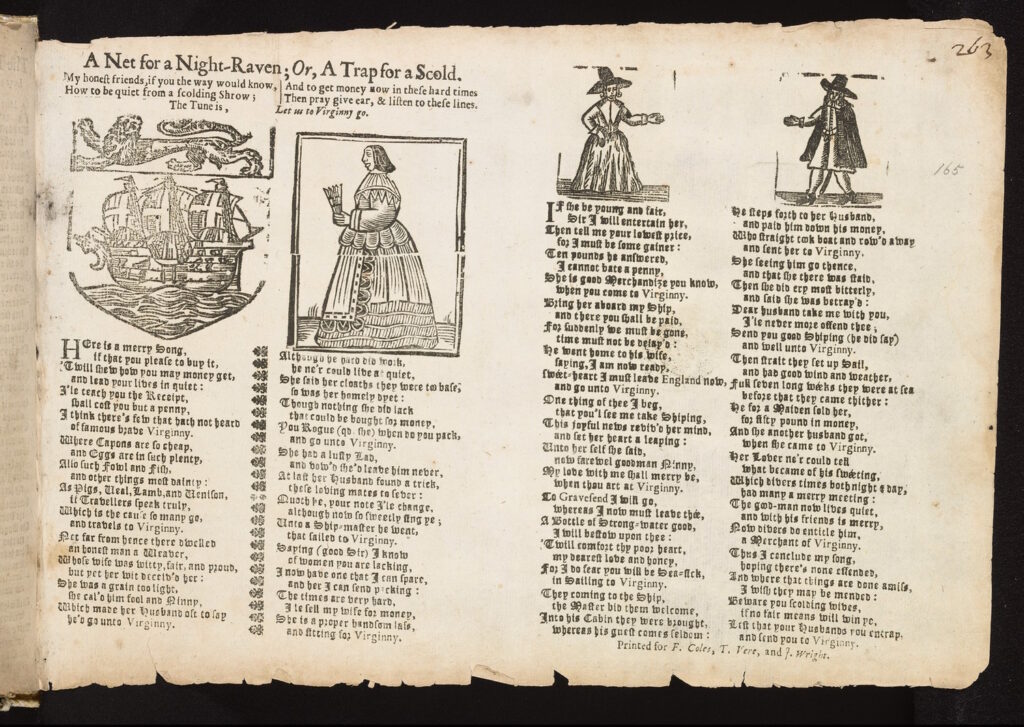

The black-letter ballad (referring to the gothic letter-type) was the most common type, with a wide range in subject matter and audience. It was generally printed on poor quality paper and on small sheets, and usually appears in a ‘landscape’ orientation. The ballads printed here were generally the length of three to five columns, though sometimes two separate ballads would be printed on one sheet. These were often cut and cold separately (as slip songs). They were among the cheapest types of print, yet they were relatively expensive still in comparison to white-letter ballads, presumably because they were often illustrated with woodcuts. Looking at the cost per page, the black-letter ballad was even expensive relative to pamphlets, for both the reader and the printer.

The white-letter ballad referred to ballads printed with roman type, in portrait orientation and with an abundance of white space on the sheet instead of woodcut illustrations. The size and quality of the paper were generally better than those of the black-letter ballads. The subject range was considerably smaller, however. Until the 1670s the white-letter ballad form was used almost exclusively for songs that contained political satire.

Oftentimes there was no strict relation between a particular song and a particular melody. Melodies were reused for new songs, sometimes because the tune was popular and sometimes to make an explicit reference to the content of an earlier (satirical) song. We can recognize most early modern songs through an indication of the tune, either in the form of musical notation or a note detailing that the song is to be sung to the tune of another particular song. Another possibility is through the layout in different verses, often indicated with an empty line between verses or a jump in the margins at the beginning of a new verse.

In the Dutch Republic songs were printed in song books as well as broadsheets. Many of these song books had small formats (16mo; 12mo) and can be considered as cheap print as well. They covered a wide range of topics, including love songs, religious songs, political songs etc.

Song books also occurred in Germany, France, England and Spain, but not all of them were aimed at a broad audience. German songs occurred both in a broadside form and as quarto pamphlets (containing a few songs). In Germany the ‘Bänkelsänger’ (‘Bench-singer’) was a popular, performative, phenomenon. These street singers used a big cloth with painted scenes on it, that illustrated the song. While the singer sang the song, his companions sold the printed sheets. French songs often appeared first as a single sheet to be included in cheap songbooks (‘recueils’) later. The term vaudeville also occurs in titles of early modern French song books, but this term has now come to be associated with the theatrical genre that emerged in the 19th century.

In Italy, songs were printed in the form of small ‘books’ or ‘pamphlets’ (quarto format), usually containing one song. Printed on very poor paper and of poor typographical quality, most of them would have been sung or recited by cantastorie/cantimbanchi (‘story-singers/ bench singers’) and then sold. Sometimes the name of the melody to which the text can be sung is indicated, and sometimes there is a reference to the fact that it was ‘recited’. They cover a huge range of subjects/genres: from laments to celebrations or news of battles or weddings; witty dialogues and satires, moralising and pedagogical texts and so on. Many still survive in Italian libraries from the late 1520s-1530s and the ‘genre’ flourished throughout the century and into the next. Cantari were a specific subcategory of Italian ballads. It was a very popular form of oral poetry in Italy from the mid-14th century onward. These cantari were narrative texts in ottava rima, about forty stanzas long. They were orally performed in public by street singers, but they are also preserved in written and printed form. They cover many topics: chivalric tales, ancient and recent battles, current affairs, legends, religious stories, moral topics, novelle and fairy tales etc. They were also sung on the streets.

In Spain, the equivalent of the European ballad is the romance, a form whose longevity spans the period from the fifteenth century until almost the present day. It is a type of song defined by its metre: a series of octosyllabic lines, with pairs of lines having assonant endings. Although many romances were printed from the sixteenth century onwards, the impact of oral delivery on their creation and transmission remained constant over the years: a vast number of them were unpublished and crossed the centuries through oral communication, and for those which were printed orality played a central role in the way they were written and performed.

In Spain (as well as Portugal and colonial America), villancicos were a popular poetic and musical form from the late 15th to the 18th century. Initially profane in nature, they gained currency especially as devotional songs in the 17th century. They started to appear in print in the first half of that century. They were sung during matins of religious feasts (the term is still used in present-day Spanish to designate Christmas carols).

Related terms

broadside ballad, song sheet, street song, slip song, song book, lament, criminal narrative, martyr story, libel/pasquil

Sources

M. Alvar, El romancero: tradicionalidad y pervivencia (Barcelona: Planeta, 1974).

M. Bendinelli Predelli, ‘Italian Cantari’, in: Oxford Bibliographies 2016. DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195396584-0199

W.L. Braekman, ‘Dutch Black Letter Ballads of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’, Quaerendo 4 (1974), 132-142.

W.L. Braekman, ‘Dutch Black Letter Ballads of the Seventeenth Century’, Quaerendo 11 (1981), 179-196.

S. G. Brandtzæg and Karin Strand. Skillingsvisene I Norge 1550-1950: Studier I En Forsømt Kulturarv. (Oslo: Spartacus Forlag AS / Scandinavian Academic Press, 2021).

S.G. Brandtzæg & K. Strand, ‘The Scandinavian Skilling Ballad: A Transnational Cultural Heritage’, in: Cheap Print and the People: European Perspectives on Popular Literature, ed. D. Atkinson & S. Roud (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019), 139–169.

Broadside Ballads Online, Bodleian Libraries, http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/

R.W. Brednich, Die Liedpublizistik im Flugblatt des 15. bis 17. Jahrhunderts, 2 vols. (Baden-Baden: Koerner, 1974-1975).

G. Caravale, ‘Censura e pauperismo tra cinque e seicento’, Rivista di Storia e Letteratura Religiosa 38:1 (2002), 39-77.

C.M. Collantes Sánchez, I. Casas Delgado (eds.), Literatura de cordel en la sociedad hispánica (siglos XVI-XX) (Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, 2022).

O. Cox Jensen, The Ballad-Singer in Georgian and Victorian London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

R. Darnton, ‘An Early Information Society: News and the Media in Eighteenth-Century Paris’, American Historical Review 105 (2000), 1-35, esp. 19-30.

L. Degl’Innocenti, ‘I cantari in ottava rima tra Medio Evo e primo Rinascimento: i cantimpanca e la piazza’, in: M. Agamennone (ed.), Cantar ottave. Per una storia dell’intonazione cantata in ottava rima (Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana, 2017), 3-24.

English Broadside Ballad Archive (EBBA), Early-Modern Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu

J. Díaz, El Ciego y Sus Coplas: Selección de Pliegos en el Siglo XIX, (Madrid: Escuela Libre Editorial, 1996).

A. Fox, The Press and the People: Cheap Print and Society in Scotland, 1500-1785 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), chapter 8: ‘Ballads and Songs’.

P. Fumerton, The Broadside Ballad in Early Modern England. Moving Media, Tactical Publics (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).

P. Fumerton, A. Guerrini, K. McAbee (eds.), Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500-1800 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

P. Fumerton, P. Kosek, and M. Hanzelková (eds.), Czech Broadside Ballads as Text, Art, and Song in Popular Culture, ca. 1600–1900. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463721554_ch01

J. Gomis, Menudencias de imprenta. Producción y circulación de la literatura popular (Valencia, siglo XVIII) (Valencia: Alfons el Magnànim, 2015).

S. González-Sarasa Hernáez, Tipología editorial del impreso antiguo español, thesis Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2013), 369-373 (‘Villancico’). https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/24020/

L.P. Grijp, Het Nederlandse lied in de Gouden Eeuw (Amsterdam: P.J. Meertens-Instituut, 1991).

P. Hainsworth and D. Robey (eds.), The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

A.J. Harper, German Secular Song-Books of the Mid-Seventeenth Century: An Examination of the Texts in Collections of Songs Published in the German-Language Area between 1624 and 1660 (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate, 2003).

H. Horstbøll, Menigmands Medie: Det Folkelige Bogtryk I Danmark 1500-1840. En Kulturhistorisk Undersøgelse. Danish Humanist Texts and Studies, V. 19. (København: Kongelige bibliotek, 1999).

J. Hyde, Singing the News: Ballads in Mid-Tudor England (London: Taylor and Francis, 2018).

J. Hyde, J. Raymond, M. Rospocher, Y. Ryan, A. Schaffer, H. Salmi, Communicating the News in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge Elements series (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming 2023).

M.-D. Leclerc, A. Robert (eds.), Chansons de colportage (Reims: Presses Universitaires de Reims, 2002).

D. Lohmeier, ‘Die Verbreitingsform des Liedes im Barockzeitalter‘, Daphnis. Zeitschrift für Mittlere Deutsche Literatur 8 (1979), 41-65.

U. McIlvenna, ‘Ballads of Death and Disaster: The Role of Song in Early Modern News Transmission’, in: J. Spinks and C. Zika (eds.), Disaster, Death and the Emotions in the Shadow of the Apocalypse, 1400-1700 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 275-294.

U. McIlvenna, S. Gøril Brandtzæg, J. Gomis, ‘Singing the News of Punishment: The Execution Ballad in Europe, 1550-1900’, Quaerendo 51 (2021), 123-159.

U. McIlvenna, Singing the News of Death: Execution Ballads in Europe 1500-1900 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

A. McShane, ‘Ballads and Broadsides’, in: J. Raymond (ed.), The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 339-362.

A. McShane, Political Broadside Ballads of Seventeenth- Century England: A Critical Bibliography (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2011).

S. Moisi, Das politische Lied der Reformationszeit (1517-1555). Ein Beitrag zur Kommunikationsgeschichte des Politischen im 16. Jahrhundert, PhD thesis, University of Graz, 2015.

C. de Morrée, ‘De la musique sans notes au XVIe siècle: chansonnier, parolier, recueil de poèmes’, Histoire du livre. Blog scientifique de la Société Bibliographique de France, 23 June 2019, https://histoirelivre.hypotheses.org/4249 (accessed 22 March 2023).

C. de Morrée, ‘Fashions of Old and New Songs. French Popular Songbooks around 1535’, Book History 26 (2023), 1-47.

Nederlandse Liederenbank, Meertens Instituut, http://www.liederenbank.nl/

P.-L. Niinimäki, Saa veisata omalla pulskalla nuotillansa. Riimillisen laulun varhaisvaiheet suomalaisissa arkkiveisuissa. (Tampere: Suomen Etnomusikologinen Seura, 2007).

T. Plebani, ‘Voci tra le carte. Libri di canzoni, leggere per cantare’, in: L. Braida and M. Infelise (eds.), Libri per tutti: generi editoriali di larga circolazione tra Antico Regime ed Età contemporanea (Turin: UTET/Novara: De Agostini, 2016), 57-76.

C. Rose Livingston, British Broadside Ballads of the Sixteenth Century (New York: Garland,1991).

Roud Folk Song Index: https://www.vwml.org/song-subject-index

R. Salzberg and M. Rospocher, ‘Street Singers in Italian Renaissance Urban Culture and Communication’, Cultural and Social History 9:1 (2012), 9-26.

K. Sisneros, ‘Early Modern Memes: The Reuse and Recycling of Woodcuts in 17th-Century English Popular Print’, The Public Domain Review, 6 June 2018, https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/early-modern-memes-the-reuse-and-recycling-of-woodcuts-in-17th-century-english-popular-print

T. Storey, Carnal Commerce in Counter Reformation Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 25-56.

A. Tacaille, L’air et la chanson: les paroliers sans musique au temps de François Ier, habilitation à diriger des recherches, Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 2015. https://hal.science/tel-02299475/ (accessed 3 April 2023).

T. Laine, ’Arkkiveisut’, in: Vanhimman suomalaisen kirjallisuuden käsikirja (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1997).

VDLied: Union Catalogue of Digitized German Song Pamphlets: https://uri.gbv.de/database/vdlied

N. Veldhorst, Zingend door het leven. Het Nederlandse liedboek in de Gouden Eeuw (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009).

T. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

M. De Wilde, De lokroep van de nachtegaal. Wereldlijke liedboeken uit de Zuidelijke Nederlanden (1628-1677) (Antwerp: University of Antwerp, 2011).

B. Wilson, Singing Poetry in Renaissance Florence: The ‘Cantasi Come’ Tradition and Its Sources (Florence: Olschki, 2009).