Glossary

Chapbook

Other languages

- Dutch: volksboek, blauwboekje

- French: livre bleu, livret de colportage

- German: Volksbuch

- Italian: libro da risma, libro di larga diffusione, libro popolare, libro di larga circolazione

- Polish: broszura, druk straganowy, druk jarmarczny, druk popularny

- Spanish: literatura de cordel, pliegos de cordel, pliegos sueltos

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Games and humour, Music and performative literature, Narrative literature and history, Religion and moralityDescription

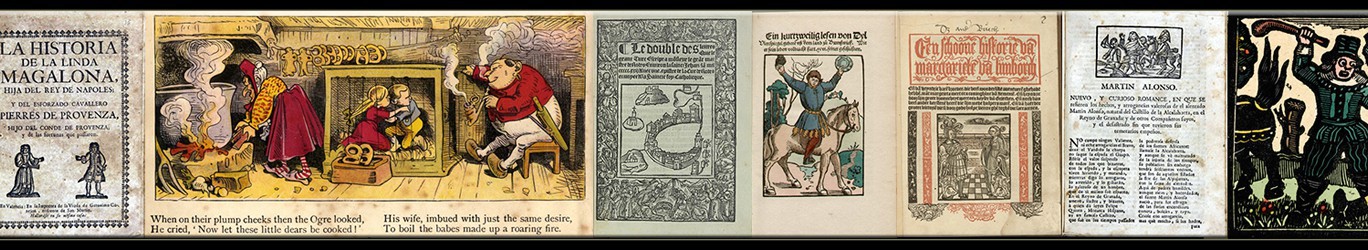

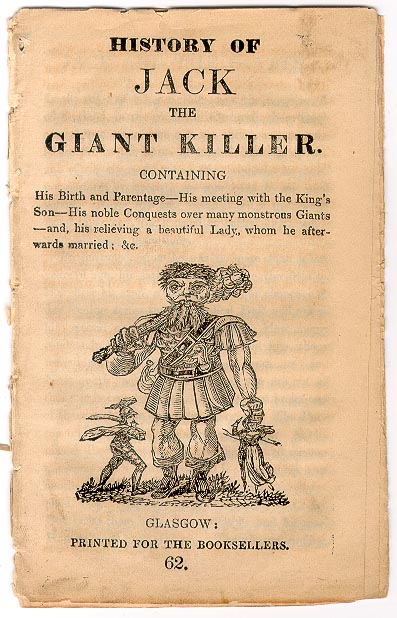

The term chapbook is used in scholarship in a double sense: first, as a collective term to indicate cheaply printed booklets, similar to terms like street literature, pièce gothique or livre bleu (France), blauwboekje or volksboek (Dutch), libri da risma (Italian), Kolportageliteratur or Volksbuch (German), literatura de cordel or pliegos sueltos (Spanish). Secondly, the term refers to a specifically British and American genre that consisted of booklets usually produced from one or one and a half sheets of paper, folded in 24 or 36 pages (though sometimes more sheets could be used). Crudely printed, they usually had a woodcut on the title page, often reused from a printer’s stock. They were printed mainly in British provincial towns and sold for a penny or less, but longer and more refined items could reach the price of six pence. They were usually sold by itinerant pedlars, ‘chapmen’, from which the genre name originated, in use from the late 18th century. The book type already existed since the 16th century, when they were also available in shops. As far as content is concerned, they could contain tales of romance, books of jests, prophecies, moral or pious materials, crime narratives or humour. A patter was as specific type of chapbook. Usually an 8 or 16-page publication containing simple religious texts, humorous or sensational stories such as accounts of murders or natural disaster. Sold by a patterer or streetseller.

In France, the bibliothèque bleue is a collective term – coined around 1700 – for small, cheaply printed books that were typically published with a blue paper cover. The format was introduced in 1602 in Troyes by the brothers Jean and Nicolas Oudot and was quickly adopted by other printers across France. The books ranged from chivalric novels to almanacs and from conduct manuals to fairy tales. Initially they were mostly sold within the cities, but by the late 17th century they were also widely sold by colporteurs (pedlars) in the countryside. In Troyes, the Bibliothèque bleue continued as a family business of Jean Oudot’s descendants until 1760, when the Oudots sold their inventory to their local competitor, the Garnier family. The format of the ‘blue books’ remained popular throughout the 19th century.

In 18th-century Italy, the Venetian Remondini family were the largest printing firm of small and cheap books, called libri da risma because they were sold unbound and at a fixed price per ream (500 paper sheets).

The Spanish collective term literatura de cordel was coined by scholars in the late 19th century, referring to the way cheap books were offered by pedlars: hanging from a string (cordel). Likewise, pliegos sueltos is not a contemporary term either, and its use is debated among scholars. In a strict sense it refers to a single folded sheet of paper close to today’s A3 size, resulting in an 8-page pamphlet in quarto format. However, this meaning was broadened as scholars started to use the term to refer to prints of 12, 24, 36 or even more pages.

A long-time popular category in Spain was the pliego poético, a booklet in quarto (sometimes octavo) that contained a narrative in verse. They were sold unbound and were often illustrated. Their thematic variety was very broad, including traditional lyrical poetry, fictional or historical narratives, riddles, and religious subject matter, among other things. They appeared from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. Somewhat similar in form and broad thematic scope to Italian cantari (see Ballad), they were regularly performed (though apparently recited rather than sung) and sold in the streets. The pliego poético is especially associated with blind itinerant sellers.

Related terms

children’s chapbook, romance, devotional literature, jestbook, criminal narrative, patter

Sources

L. Andries, La bibliothèque bleue: littérature de colportage (Paris: R. Laffont, 2003).

H.M.C.W. Blom, « Vieux romans » et « Grand Siècle » : éditions et réceptions de la littérature chevaleresque médiévale dans la France du XVIIe siècle, dissertation Utrecht University, https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/224190, esp. 35-39, 156-159.

L. Carnelos, I libri da risma. Catalogo delle edizioni Remondini a larga diffusione (1650-1850) (Milan: FrancoAngeli, 2008).

L. Carnelos, ‘Con libri alla mano’. Editoria di larga diffusione a Venezia tra Sei e Settecento (Milan: Unicopli, 2012).

P.M.H. Cuijpers, Van Reynaert de Vos tot Tijl Uilenspiegel: op zoek naar een canon van volksboeken, 1600-1900 (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2014).

T. Delcourt and E. Parinet (eds.), La Bibliothèque Bleue et les littératures de colportage (Paris: École des chartes / Troyes: La Maison du Boulanger, 2000).

A. Fox, ‘“Little Story Books” and “Small Pamphlets” in Edinburgh, 1680–1760: The Making of the Scottish Chapbook’, The Scottish Historical Review 92:2 (Oct. 2013), 207-230.

A. Fox, The Press and the People: Cheap Print and Society in Scotland, 1500-1785 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

M.A. García Collado, ‘Los pliegos sueltos y otros impresos menores’, in: V. Infantes, F. López, and J.F. Botrel (eds.) Historia de la edición y de la lectura en España: 1472-1914 (Madrid: Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruipérez, 2003), 368-377.

S. González-Sarasa Hernáez, Tipología editorial del impreso antiguo español, thesis Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2013), 419-423 (‘Poético, pliego’). https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/24020/

Ch. Hindley, The True History of Tom and Jerry (London: Charles Hindley, 1886).

B. McKay, An Introduction to Chapbooks (Oldham: Incline Press, 2003).

J. Meriton, with C. Dumontet, Small Books for the Common Man. A Descriptive Bibliography (London: British Library/New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2010).

‘National Art Library Chapbooks Collection’, website Victoria and Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/n/national-art-library-chapbooks-collection/ (accessed 7 April 2023).

V.E. Neuburg, Chapbooks: A Guide to Reference Material on English, Scottish and American Chapbook Literature of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, 2nd ed. (London: Woburn Press, 1972).

L.H. Newcomb, ‘What is a Chapbook?’, in: A. Hadfield and M. Dimmock (eds.), Literature and Popular Culture in Early Modern England (London: Routledge, 2009), 57-72.

S. Pedersen, ‘Hannah More Meets Simple Simon. Tracts, Chapbooks, and Popular Culture in Late Eighteenth-Century England’, Journal of British Studies 25:1 (1986), 84-113.

J.-F. Potrel, ‘El género de cordel’, in: L. Díaz G. Viana (ed.), Palabras para el pueblo, vol. 1: Aproximación general a la literatura de cordel (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2001), 41-69.

F.J. Potter, Gothic Chapbooks, Bluebooks and Shilling Shockers, 1797-1830 (Cardiff: University of Wales, 2021).

M. Pouspin, Publier la nouvelle: Les pièces gothiques, histoire d’un nouveau média (xve-xvie siècles) (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2016), http://books.openedition.org/psorbonne/27156.

C.L. Preston, M.J. Preston, The Other Print Tradition. Essays on Chapbooks, Broadsides, and Related Ephemera. New York [etc.]: Garland, 1995.

M. Spufford, Small Books and Pleasant Histories: Popular Fiction and Its Readership in Seventeenth-Century England (London: Methuen, 1981).

T. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).