Glossary

Devotional literature

Other languages

- Dutch: devotieboek, devotieprent, getijdenboek

- French: livre de spiritualité, livre de piété, livre de dévotion, livre de prière, livre liturgique, image de dévotion

- German: Erbauungsliteratur, Stundenbuch, Andachtsbild

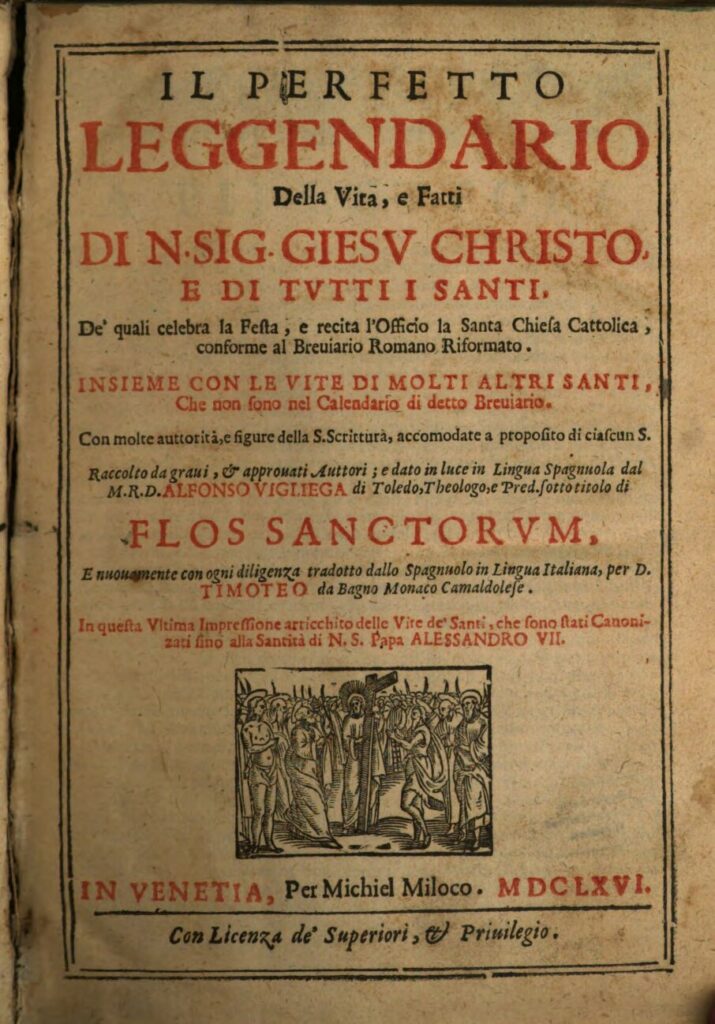

- Italian: libro di devozione, devozionale, libro spirituale, libro di pietà, libro di preghiere, ufficiolo, libro d’ore, leggendario, libro per l’anima

- Polish: literatura dewocyjna, literatura pobożnościowa

- Spanish: libro de devoción, devocionario, cartel de devoción, libro de horas

Material form

Printed book, Single-sheet printSubject

Music and performative literature, Religion and moralityDescription

Devotional literature accounted for a major stream of steady sellers across Europe from the early days of print onwards, initially with many titles that already circulated in manuscript. This broad category included many different genres, notably bibles (in full or just the New Testament or the Gospels), psalters, prayer books, catechisms, lives of saints and martyrs, meditations, sermons, exegesis, all kinds of moral-didactic books intended as manuals for a virtuous life such as household manuals, and all kinds of devotional broadsides. By no means all of these publications can be considered popular in the sense of cheap; genres such as bibles, psalters, lives of saints and household manuals appeared in small and simple formats just as well as in luxurious, large, and/or lavishly illustrated editions. However, as Peter Lake (2011, 220) observes, many types of text, ‘while too long and expensive to deserve the soubriquet cheap, were produced on so massive a scale and were so ubiquitously present as to demand inclusion in any discussion of popular religion.’ Many devotional books explicitly targeted lay readers and were published in the vernacular and in a small size. From the Reformation onward, most devotional publications had a decidedly confessional character.

What all devotional genres have in common is their aim to be used for personal worship and spiritual instruction. This aim distinguishes them from theological or politico-religious literature, although boundaries are not always clear-cut. For example, confessional literature could certainly carry political connotations, and religious broadsides such as ballads and images of biblical stories could serve devotional and entertainment purposes alike. Indeed, Lake considers the intermingling of the religious/devotional and the profane as ‘an abiding feature of much of the cheap print of the period’ (2011, 230), from plague treatises to tidings of extreme weather and monster births and other events that were interpreted as divine messages.

For England, Tessa Watt uses the term ‘penny godlies’ or ‘penny godlinesses’ to describe a genre of mostly Protestant chapbooks that provided advice on leading a pious life, of which she traces the origins to the 1620s (Watt 1991, 303-320).

In Italy, from the mid-16th century, the fight against Protestant propaganda and its extensive use of the vernacular press led to religious texts in Italian being considered potentially dangerous and often tainted with heresy. As a result of increasing censorship and bans, not only the Bible in Italian but also most of the vernacular books related to Holy Scripture (Epistole and Evangeli, Passion stories, collections of sermons, etc.) were no longer allowed.

To ensure both the control of beliefs and the uniformity of worship practices, the Church of Rome relied instead on the dissemination of catechisms and doctrines. But alongside these grew a highly spectacular and emotional devotional and hagiographic literature, full of lives of saints, martyrs and hermits; of litanies, orations and indulgences; of Giardini dell’anima, Orologi spirituali e Vie crucis. The success of such products (books, booklets and flyers) with the popular public was favoured by their low cost, small format and the brevity of the texts. The preferential use of verse over prose also contributed, with forms of communication facilitated by music and song.

In addition to devotional books and booklets, woodcut prints and other broadsides with devotional content were widespread across Europe. They included images of saints, biblical scenes (e.g. the Crucifixion or, in later centuries, penny prints with bible stories told in a sequence of images), prayers or hymns, for example.

In Spain, typical genres of religious prints were the estampas and gozos or goigs. Estampas were folio or quarto sheets printed on one side with an image of a saint. They “were of a religious nature and fulfilled a devotional, thaumaturgical, and doctrinal function”, while gozos (in Castilian) or goigs (in Catalan) were “leaflets with hymns corresponding to a particular religious appellation, which is represented in a picture of greater or smaller size” (Botrel and Gomis 2019, 130). As a consequence of strict control and restrictions in the second half of the 16th century, the production of devotional literature was relatively modest in Spain, while much material was imported.

The Spanish carta del cielo was a short piece of printing of one or two sheets in quarto with a large devotional image, and a short text that was written as if it constituted a letter by God or the Virgin themselves that was transmitted through an angel or another supernatural means. These divine messages were attributed magical or healing powers. As they were increasingly produced with a focus on financial gain from indulgences rather than on devotion, they became a subject of criticism and censorship. Nevertheless, they continued to be produced until well into the 19th century.

Related terms

catechism, prayer book, sermon, chapbook, ballad, household manual, broadsheet, martyr story

Sources

D.S. Areford, The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

J.-F. Botrel and J. Gomis, ‘“Literatura De Cordel” from a Transnational Perspective. New Horizons for an Old Field of Study’, in: M. Rospocher, J. Salman and H. Salmi (eds.), Crossing Borders, Crossing Cultures. Popular Print in Europe (1450–1900) (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019), 127-142.

A. Brundin, D. Howard, M. Laven (eds.), The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

U. Brunold-Bigler, ‘Erbauungsbuch’, in: Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens Online, http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004337862__COM_050465

J. Bryan, Looking Inward. Devotional Reading and the Private Self in Late Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

G. Caravale, L’orazione proibita (Firenze : Olschki 2003).

L. Carnelos, ‘Con libri alla mano’. Editoria di larga diffusione a Venezia tra Sei e Settecento (Milan: Unicopli, 2012).

S. Corbellini, M. Hoogvliet, B. Ramakers (eds.), Discovering the Riches of the Word: Religious Reading in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2015).

A. Dlabačová, ‘Printed Pages, Perfect Souls? Ideals and Instructions for the Devout Home in the First Books Printed in Dutch’, Religions 11 (2020), [n.p.].

A. Dlabačová and M. Hoogvliet, ‘Religieuze literatuur tussen het Middelnederlands en het Frans. Tekstuele mobiliteit en gedeelde leescultuur’, Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde 136:3 (2020), 99-129.

M. Faini and A. Meneghin (eds.), Domestic Devotions in the Early Modern World (Leiden: Brill, 2019).

G. Fragnito, La Bibbia al rogo (Bologna: il Mulino 1997).

S. González-Sarasa Hernáez, Tipología editorial del impreso antiguo español, thesis Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2013), esp. Chapter 2, ‘Productos editoriales de devoción y culto (127-138) and 303-373. https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/24020/

I. Green, ‘The Laity and the Bible in Early Modern England’, in: R. Armstrong and T. Ó Hannracháin (eds.), The English Bible in the Early Modern World (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 53-83.

F.M. Higman, Piety and the People. Religious Printing in French, 1511–1551 (Aldershot: Scolar Press Bookfield, 1996).

J. van der Laan, Enacting Devotion: Performative Religious Reading in the Low Countries (ca. 1470-1550), dissertation University of Groningen, 2020, https://doi.org/10.33612/diss.130758161.

P. Lake, ‘Religion and Cheap Print’, in: J. Raymond (ed.), The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 217-241.

J. Martin and A. Ryrie (eds.), Private and Domestic Devotion in Early Modern Britain (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012).

P. Martin, Une religion des livres (1640-1850) (Paris: les Éditions du Cerf, 2003).

P. Martin, Produire et vendre des livres religieux: Europe occidentale, fin XVe siècle-fin XVIIe siècle (Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 2022).

A. Pettegree, The Book in the Renaissance (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2010).

M. Pouspin, Publier la nouvelle: Les pièces gothiques, histoire d’un nouveau média (xve-xvie siècles) (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2016), http://books.openedition.org/psorbonne/27192, chapter 7: ‘Les livrets de dévotion’.

M. Roggero, Le vie dei libri. Letture, lingua e pubblico nell’Italia moderna (Bologna: il Mulino, 2021).

U. Rozzo and R. Gorian (eds.), Il libro religioso (Milan: Sylvestre Bonnard, 2002).

P. Rueda Ramírez, ‘Efímeros de fe: estrategias de distribución de impresos y estampas devotas en Cataluña (siglos XVII-XVIII)’, La Bibliofilia 121:2 (2019), 327-349.

A. Serrano Dura, A Transnational Study of Eighteenth-Century English Street Literature and Spanish literature de cordel: Cluer Dicey and Augustin Laborda, Tesis Doctoral (Valencia: Universidad Católica de Valencia, 2021).

A. Sinclair, ‘The Elephant in the Room? Religion in the pliegos sueltos of Peninsular Spain’, Bulletin of Spanish Studies 96 (2019) 9-10.

A. Thijs, Antwerpen internationaal uitgeverscentrum van devotieprenten, 17de-18de eeuw. Miscellanea Neerlandica, 7 (Leuven: Peeters, 1993).

T. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

A.S. Wilkinson, A. Ulla Lorenzo and A. de la Cruz, ‘A Survey of Printed Spanish Broadsheets, 1472–1700’, in: A. Pettegree (ed.), Broadsheets: Single-Sheet Publishing in the First Age of Print (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2017), 55-75, esp. 67-69.