Glossary

Household manual

Other languages

- French: livre de ménage, manuel de conduite, manuel familial, manuel conjugal

- German: Hausväterliteratur, Ehespiegel

- Italian: trattato di economia domestica, precettistica, manuali di condotta

- Polish: poradnik gospodarski, poradnik domowy (early modern term: ekonomia, oeconomia)

- Spanish: manual de urbanidad

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Knowledge and skills, Religion and moralityDescription

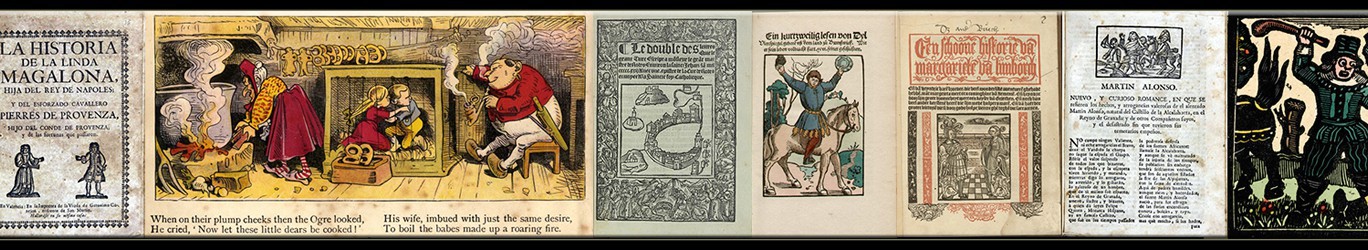

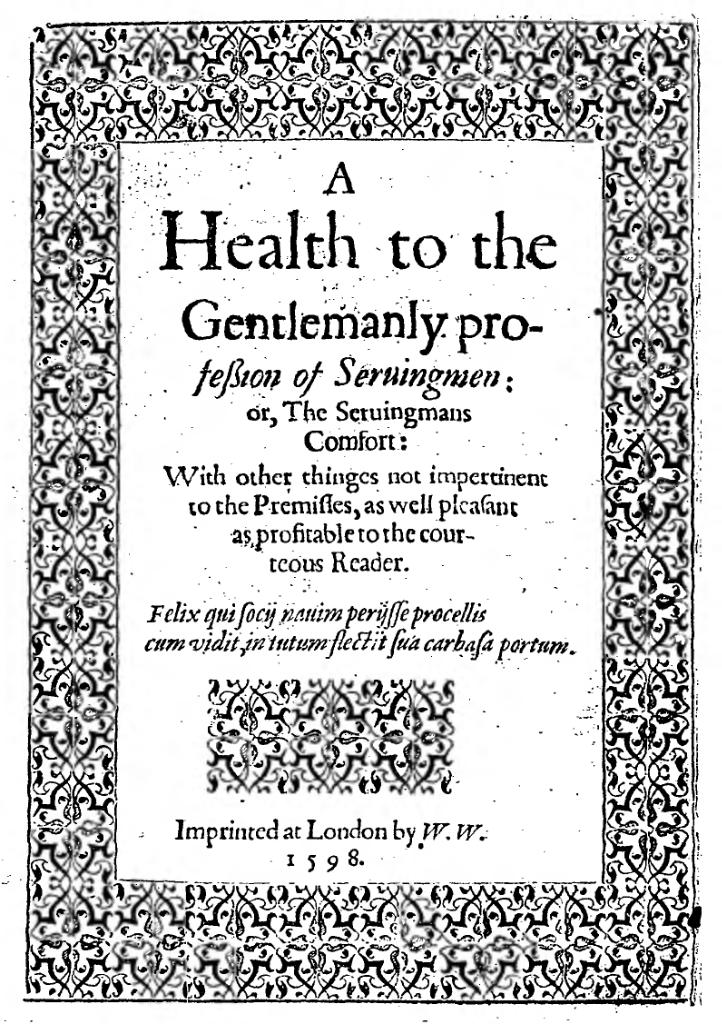

Household manuals are ‘substantial didactic texts that purport to offer their readers domestic bliss by outlining the mutual responsibilities of those who lived under the same roof’ (Richardson 2013, 169). They advised on practical how-to knowledge (e.g. recipes, husbandry, domestic labour), on devotional practices within the home, and/or on the appropriate conduct for husbands, wives, and other household members. Moralising and practical instruction were frequently combined. As Richardson notes, ‘the manuals attempted to tie biblical ideals to everyday practice’ (2013, 171). They contain simplified theological discourses and – especially in the confessionalization period – were meant to encourage a good life in accord with the confession.

In 17th-century England, advice books on ‘godly living’ and parent’s advice to children flourished (Morrissey 2011, 504; Watt 1991, 303-306). The motif of familial advice also appeared in other genres, such as ballads and chapbooks in which parents advised their children for example how to find a good spouse and to achieve a happy marriage (Marazzi 2020, 131-132).

Typical for the German-speaking regions were the so-called Ehespiegel (marriage mirrors) and Hausväterliteratur (household and conduct texts). Ehespiegel were of a predominantly moralising nature, discussing the ideal relationship between and respective roles of husband and wife in marriage and in the household. These works appeared in print from the 1470s on, and in the course of the 16th century they were sometimes published as collections of (Protestant) marriage sermons. Hausväterliteratur, mostly written by Protestant preachers, was especially popular in Protestant households from the late 16th century onward. It provided practical knowledge on managing a large household, including subjects such as agriculture, fishing, and cooking, as well as practical and sometimes also moralising advice on the relationships within the household, not only between husband and wife and parents and children, but also masters and servants. These how-to books were aimed primarily at noble and upperclass households, although it is likely that its content spread in broader layers of the population (Lemmer 1991, 183-184). Some of these household manuals explicitly include the servants in their intended audience.

Partially related in subject matter and aimed at the broadest conceivable audience were the Noth- und Hülfsbüchlein that sold in spectacular quantities in the late 18th century (an estimated 400,000 copies by the early 19th century; Siegert 2019, 259). These were cheap books containing enlightening literature (including devotion and practical instruction on all kinds of domestic matters) for the whole population, even the most uneducated and poorest. The project was developed by the German educator Rudolph Zacharias Becker (1752-1822).

Also partially related in terms of content are the Spanish manuales de urbanidad, conduct manuals to teach children about devotional as well as social behaviour in different situations. Popular especially in the later 18th and 19th centuries, they include topics as varied as table manners, one’s conduct towards God and towards people of different ranks, rules of conversation, and games.

Related terms

domestic books, devotional literature, book of secrets, how-to book, sermon

Sources

A. Brundin, M. Laven, D. Howard, The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

S. González-Sarasa Hernáez, Tipología editorial del impreso antiguo español, thesis Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2013), 472-475 (‘Manual de urbanidad’). https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/24020/

M. Lemmer, ‘Haushalt und Familie aus der Sicht der Hausväterliteratur’, in: T. Ehlert (ed.), Haushalt und Familie in Mittelalter und Früher Neuzeit (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1991), 181-192.

E. Marazzi, ‘Children and Cheap Print in Europe: Towards a Transnational Account, 1700–1900’, in: D. Atkinson and S. Roud (eds.), Printers, Pedlars, Sailors, Nuns: Aspects of Street Literature (London: The Ballad Partners, 2020), 125-147.

C. Richardson, ‘Household Manuals’, in: E. Smith and A. Kesson (eds.), The Elizabethan Top Ten: Defining Print Popularity in Early Modern England (London/New York: Routledge, 2013), 169-178.

R. Siegert, ‘The Greatest German Book Success of the Eighteenth Century. Rudolph Zacharias Becker’s “Noth- und Hülfsbüchlein” (1788/1798) as the Prototype of Printed Volksaufklärung and its Dissemination in Europe’, in: M. Rospocher, J. Salman and H. Salmi (eds.), Crossing Borders, Crossing Cultures. Popular Print in Europe (1450–1900), (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019), 245-263.

H. Smolinsky, ‘Ehespiegel im Konfessionalisierungsprozess‘, in: W. Reinhard (ed.), Die katholische Konfessionalisierung (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1995), 311-331.

W. Wall, ‘Literacy and the Domestic Arts’, Huntington Library Quarterly 73.3 (September 2010), 383-412.

T. Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).