Glossary

Game (printed on paper)

Other languages

- Dutch: papieren speelgoed, spelletje (specific forms: lotboek, kaartspel, ganzenbord, koningsbrieven)

- French, specific forms: jeux de cartes, livre de fortune, livre de jeux, jeu de l’oie, billets des Rois

- German: Papierspielzeug (specific forms: Brettspiel, Losbuch, Kartenspiel, Gänsespiel)

- Italian, specific forms: libro di ventura, carte da gioco, gioco dell’oca

- Polish: gra drukowana (specific forms: gąska, karty do gry, gra planszowa)

- Spanish: juguetes de papel (specific forms: juego de cartas, juego de la oca)

Material form

Printed book, Single-sheet printSubject

Games and humourDescription

Printed materials designed for play, usually according to prescribed rules.

Playing cards were printed from woodcuts already in the first half of the 15th century, which makes them (together with devotional images) one of the earliest printed materials in Europe.

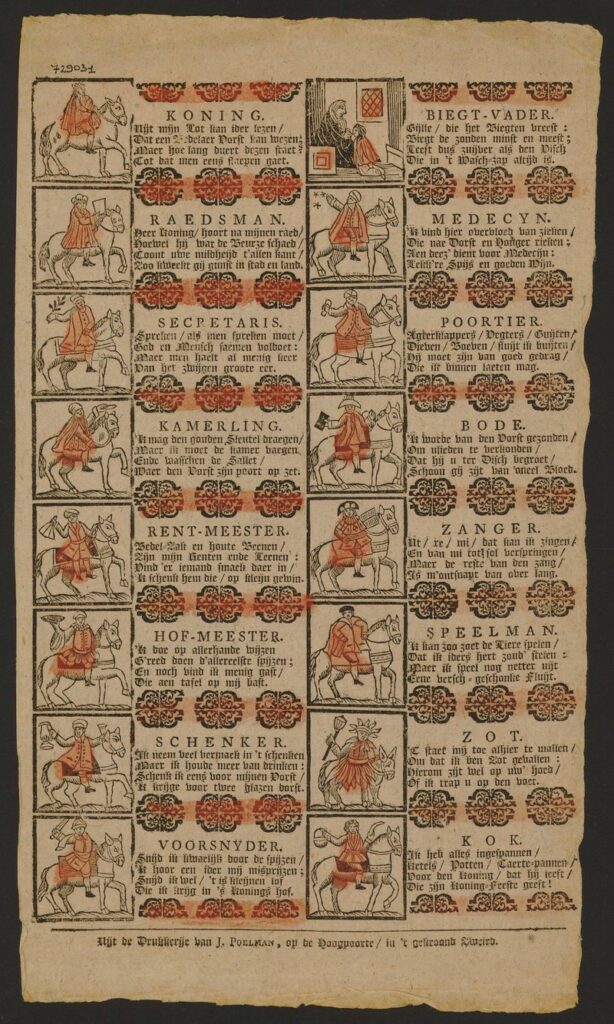

King’s letters (koningsbrieven, billets des Rois) were a particular card game, played in – as far as we know – the Dutch Republic and the southern Low Countries (present-day Belgium). In this game, one took a card which had a depiction of a certain character, such as a king, a preacher, or a joker. The cards also included a popular song or rhyme, and for that evening one had to perform the role of the card one drew, and sing the song that was printed on it. They were related to the religious feast of Epiphany (in Dutch: Driekoningen), hence their name of King’s letters. As with many other card games, such as lottery games, they were printed on large sheets which the buyers had to cut up themselves.

Books of fortune were designed to be used as interactive (group) games of fortune-telling. Their key characteristic is that fate determined how readers would proceed through the book: they first needed to turn a wheel, throw dice, pick a card, or open the book on a random page for example. Depending on the outcome, readers would end up (sometimes after several subsequent steps) at a part where their fortune was told or where they found an aphorism with life advice. Books of fortune appeared in print throughout Europe since 1482, the earliest being Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro dela ventura, but they already existed in manuscript form before that date.

The game of the goose, a board game still played in many countries to this day, existed at least since the 15th century, while similar games were already played in Antiquity. Printed boards started to appear around 1600 in Italy (oldest preserved board in Europe, 1598), England (inscribed in the Stationers’ Hall register in 1597), and France. In the Dutch Republic and Spain the oldest printed boards date from the 17th century. In the 18th century the game was increasingly also used for the education of children.

Riddle books, ballads and games were common in at least England and the Dutch Republic from the seventeenth and eighteenth century onwards. In the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic these riddles still had a religious flavour, whereas in the following century they became more secular. A rebus print, card or game contains a riddle with the aim to transfer certain images or objects in words. In the Netherlands these rebuses often appeared from the seventeenth century onwards in the form of a penny print or children’s print.

Related terms

paper toys (specific forms: board games, card games, books of fortune, playing cards, fortune telling cards, tarot cards, King’s letters, game of the goose)

Sources

A. Seville, The Cultural Legacy of the Royal Game of the Goose: 400 Years of Printed Board Games (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

W.L. Braekman, ‘Rethoricaal orakelboek op rijm’, Jaarboek De Fonteine 1980-1981 part 1, 5-36.

P.J. Buijnsters, and L. Buijnsters-Smets, Papertoys: Speelprenten en papieren speelgoed in Nederland (1640-1920) (Zwolle: Waanders, 2005).

S. González-Sarasa Hernáez, Tipología editorial del impreso antiguo español, thesis Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2013), 415-416 (‘Juego de la oca’). https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/24020/

M. Heiles, B. Reich, M. Standke (eds.), Gedruckte deutsche Losbücher des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts, vol. 1 (Oldenburg: S. Hirzel Verlag, 2021).

J. Kiliańczyk-Zięba, ‘In Search of Lost Fortuna. Reconstructing the Publishing History of the Polish Book of Fortune-Telling’, in: F. Bruni and A. Pettegree (eds.), Lost Books: Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 120-143.

E. Marazzi, ‘Cheap Toys for All in Nineteenth-Century Europe’, Journal of Interactive Books 1 (2022), 132-146. https://jib.pop-app.org/index.php/jib/article/view/38/20

J. Meriton, with C. Dumontet (eds.), Small Books for the Common Man. A descriptive bibliography (London and New Castle, DE: British Library and Oak Knoll Press, 2010).

A. Milano (ed.), Colporteurs. I venditori di stampe e libri e il loro pubblico (Milan: Medusa 2015), 7-45.

R. O’Bryan (ed.), Games and Game Playing in European Art and Literature, 16th-17th Centuries (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

J.L. Salman, ‘Playing Games with the Financial Crisis of 1720. The April Card in Het groote tafereel der dwaasheid’, in: W. N Goezmann, C. Labio, K. G Rouwenhorst, & T. G Young (Eds.), The Great Mirror of Folly. Finance, Culture, and the Crash of 1720 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 235-247.

C. Sanchez, Les livres de jeux aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: une typologie des lecteurs-joueurs, MA thesis, Université Lyon II, 2014.

J. Shefrin, ‘Ingenious Contrivances’: Table Games & Puzzles for Children. A Catalogue Based on an Exhibition at the Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books (Toronto: Friends of the Osborne & Lillian H. Smith Collections, Toronto Public Library, 1996).

C. Sinninghe Damsté-Hopperus Buma, ‘Het leven is een ganzenspel’, De Boekenwereld 34:4 (2018), 78-85.

E. Vander Straeten, Les Billets Des Rois En Flandre: Xylographie, Musique, Coutumes (Ghent: Vuylsteke, 1892).