Glossary

Children’s book and schoolbook

Other languages

- Dutch: kinderboek, schoolboek

- French: littérature de jeunesse, livre d’enfant, livre pour enfants, littérature enfantine (formerly used in scholarship), livre d’école, livre scolaire

- German: Kinderbuch, Schulbuch

- Italian: letteratura per ragazzi, libro per bambini, letteratura per l’infanzia, libro di scuola, libro scolastico, letteratura didattico-educativa

- Polish: książka dla dzieci, podręcznik szkolny

- Spanish: literatura infantil, literatura juvenil, literatura para niños

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Games and humour, Knowledge and skills, Narrative literature and history, Religion and moralityDescription

The earliest books printed especially for children were schoolbooks, which from the fifteenth century onward provided many printers/publishers with a steady income. Children learned to read with abecedaries, hornbooks, and catechism primers. The next stages of education involved (Latin) grammar books (e.g. Donatus, Cato), arithmetic books, exempla and other moralising stories that taught appropriate behaviour, among other things. Carnelos and Marazzi (2021, 192) observe a striking contrast between the Northern part of Europe, where a variety of educational publications (for use in school or at home) were conceived specifically for children, and Mediterranean Europe, where such publications especially for children ‘are almost untraceable before the eighteenth century.’

Apart from schoolbooks, in most Northern European countries a distinct market for children’s literature meant for entertainment did not establish until the late 17th or 18th century, and in Southern Europe by the 19th century. Children and teenagers used many kinds of books and prints that also targeted grown-ups, such as chapbooks, catechisms, prayer books, histories and romances, almanacs, paper games, jestbooks, and penny prints.

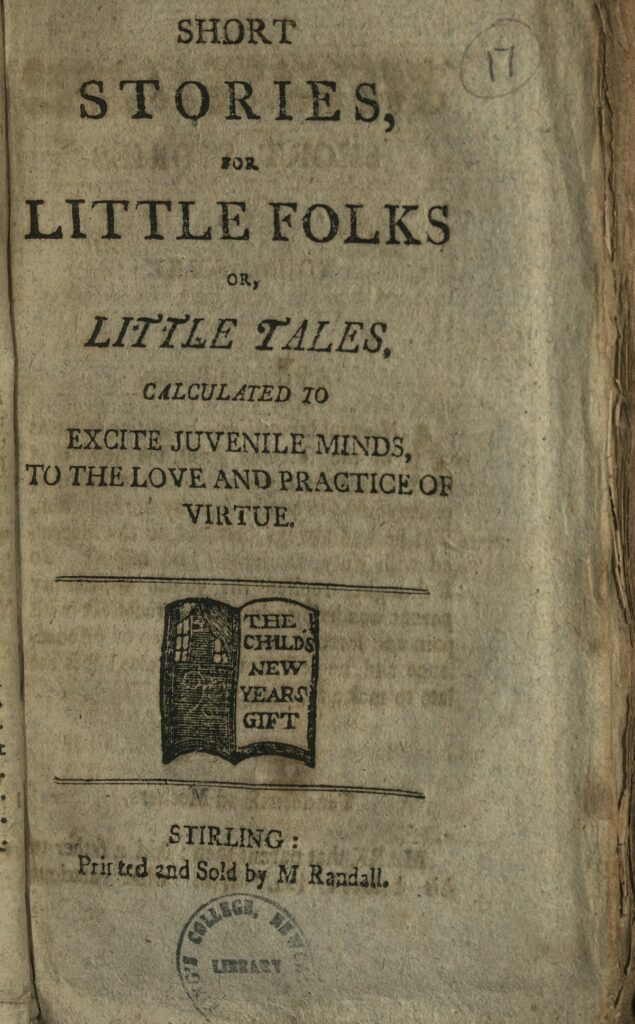

Scattered evidence shows that children were among the audience of chapbooks and perhaps this is one of the many reasons why, from the late 18th century and especially in the first decades of the 19th century, a sustained production of chapbooks for children took off in Britain. No equivalent of this particular form is known for other parts of Europe (Marazzi 2020, 130). The English children’s chapbooks did not replace other kinds of chapbooks, that might have still been read by children, but rather coexisted with them. Children’s chapbooks were usually eight, twelve, sixteen or twenty-four pages in length, but often smaller than standard chapbooks in size. They contained short moral tales, edifying fiction, alphabets, rhymes, riddles, songs, fairy stories, and legendary tales. They remained cheap, ranging from halfpenny to two-pence, but they were usually better printed than standard chapbooks. Often they included more woodcut illustrations, up to one on each page. They could be sold dab-coloured or even hand-coloured. Initially they were printed by the usual publishers of standard chapbooks, and sometimes they hardly differed from them. Soon other provincial publishers (and also some in London) developed their lines of children’s chapbook that enabled the latter to evolve into a standalone genre.

Related terms

abecedarium, hornbook, catechism primer, chapbook, penny print

Sources

V. Bold, ‘“Entertaining and Instructing Histories”: Children’s Chapbook Literature in the Nineteenth Century’, in: S. Dunnigan and S.-F. Lai (eds.), The Land of Story Books: Scottish Children’s Literature in the Long Nineteenth Century (Glasgow: Scottish Literature International, 2019), 42-62.

C. Bravo-Villasante, Historia de la literatura infantil española (Madrid: Escuela Española, 1985 [1959]).

T. Brüggemann, O. Brunken et al. (eds.), Handbuch zur Kinder- und Jugendliteratur, 5 vols (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1982-2006).

L. Carnelos and E. Marazzi, “Children and Cheap Print from a Transnational Perspective’, Quaerendo 51 (2021), 189-215.

E. Chapron, Livres d’école et littérature de jeunesse en France au XVIIIe siècle (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2021).

G. Chiosso, ‘Il libro di scuola tra editoria e pedagogia nell’Ottocento’, in: L. Braida and M. Infelise (eds.), Libri per tutti: generi editoriali di larga circolazione tra Antico Regime ed Età contemporanea (Turin: UTET/Novara: De Agostini, 2016), 203-226.

J. Cooper, ‘The Development of the Children’s Chapbook in London’, in: D. Atkinson and S. Roud (eds.), Street Literature of the Long Nineteenth Century: Producers, Sellers, Consumers, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017), 217-240.

F. Dietz, Lettering Young Readers in the Dutch Enlightenment: Literacy, Agency and Progress in Eighteenth-Century Children’s Books (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2021).

J. García Padrino, Libros y literatura para niños en la España contemporánea (Madrid: Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruipérez/Ediciones Pirámide, 1992).

M.O. Grenby, ‘Chapbooks, Children, and Children’s Literature’, The Library 8:3 (2007), 277-303.

M.O. Grenby, ‘Before Children’s Literature: Children, Chapbooks and Popular Culture in Early Modern Britain’, in: J. Briggs, D. Butts, M.O. Grenby (eds.), Popular Children’s Literature in Britain (Aldershot/Burlington: Ashgate, 2008), 25-46.

I. Havelange, ‘Des livres pour les demoiselles, XVIIe siècle-première moitié du XIXe siècle’, in: I. Brouard-Arends (ed.), Lectrices d’Ancien Régime (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2003), 575-584. https://books.openedition.org/pur/35595 (accessed 3 April 2023).

J. Hébrard, ‘Les livres scolaires de la Bibliothèque bleue: archaïsme ou modernité?’, in: R. Chartier and H.-J. Lüsebrink (eds.), Colportage et lecture populaire: Imprimés de large circulation en Europe, XVIe–XIXe siècles. Actes du colloque des 21-24 avril 1991, Wolfenbüttel (Paris: IMEC Éditions, 1996), 109-136.

N. Heimeriks, W. van Toorn (eds.), De hele Bibelebontse berg. De geschiedenis van het kinderboek in Nederland en Vlaanderen van de Middeleeuwen tot heden (Amsterdam: Querido, 1989).

F. Huguet, Les Livres pour l’enfance et la jeunesse de Gutenberg à Guizot. Les collections de la bibliothèque de l’Institut National de Recherche Pédagogique (Paris: INRP/Klincksieck, 1997).

S. Lerer, Children’s Literature: A Reading History from Aesop to Harry Potter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

P. Lucchi, ‘Leggere, scrivere e abbaco: l’istruzione elementare agli inizi dell’età moderna’, in: G. Garfagnini (ed.), Scienze, credenze occulte, livelli di cultura (Florence: Olschki, 1982), 102-119.

E. Marazzi, ‘Children and Cheap Print in Europe: Towards a Transnational Account, 1700–1900’, in: D. Atkinson, S. Roud (eds.), Printers, Pedlars, Sailors, Nuns. Aspects of Street Literature (London: Ballad Partners, 2020), 125-147.

E. Marazzi, A Shared Culture: Children and Cheap Print in Europe, 1700-1900 (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming).

V. Neuburg, The Penny Histories. A Study of Chapbooks for Young Readers Over Two Centuries (London: Oxford University Press, 1968).