Glossary

Prayer book

Other languages

- Dutch: gebedenboek, getijdenboek

- French: livre de prières, livre d’heures

- German: Gebetbuch, Stundenbuch

- Italian: libro di orazioni, orazione, libro di preghiere, preghiera

- Polish: modlitewnik

- Spanish: libro de oraciones

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Religion and moralityDescription

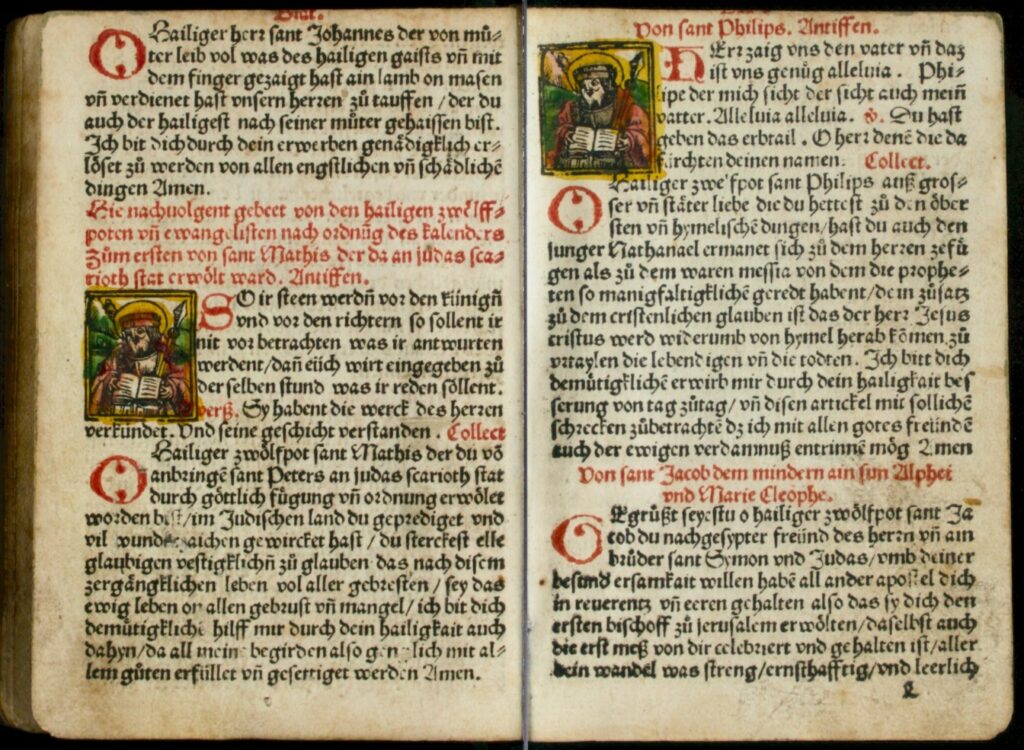

Prayer books were commonly considered aids for the conduct of church service or for personal prayer. As such they were not wholly unambiguously popular print. Especially in the pre-Reformation period, printed prayer books were published in Latin as well as vernaculars, and they could be sumptuous in execution, with illustrations or even printed on vellum. However, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries the use of (cheaper) prayer books by the laity steadily increased.

The prayer books from the 16th century were in a way a replacement of the old psalters, and included elements from the ‘book of hours’, dictating the proper hours for certain prayers, and the offices of saints, such as that of the virgin Mary. They also included psalms and readings for certain points of the day. In the Protestant tradition of prayer books these elements were lost throughout the 16th century. During the same time, the prayer books were often complemented with scriptural material, collections of prayers not commonly included in traditional prayer books, and the feast days.

Besides their obvious devotional uses, prayer books were commonly used as educational material. This education was not solely education on Christian doctrine, which was handled chiefly through the catechism. Instead, the prayer book was oftentimes used to teach children how to read, given that they were readily available, and offered relatively short texts with appropriately moral messages. The prayer book of course played an important role in forming and displaying religious identity, given that competing traditions of Protestant and Catholic prayer books existed.

A very popular prayer book in the German-speaking regions and surrounding areas in the pre-Reformation era was the Hortulus animae (or Wurzgarten or Seelengärtlein in German). It appeared in many editions from 1498 onward, all of them illustrated, in Latin and German as well as in Dutch and Polish. During the Reformation, Luther himself was involved in the publication of a Protestant counterpart that bore the same title (Hortulus animae. Lustgarten der Seelen; 1547/48).

In England, the so-called primers were initially based in particular on the Office of the Virgin Mary, with a (changing and expanding) variety of other prayers. Editions from the mid-16th century included material from the Book of Common Prayer (the authorised, Protestant liturgy). In the later 16th century the primer diminished in popularity, due to its association with Catholicism. It survived only in an abbreviated form as part of the popular catechism primer (Morrissey 2011, 495-496). By that time, the Book of Common Prayer had become the most important devotional work for the laity in England, used during services as well as in private settings.

Related terms

devotional literature, primer

Sources

T. Clemens, De godsdienstigheid in de Nederlanden in de spiegel van de katholieke kerkboeken, 1680-1840 (Tilburg, Tilburg University Press, 1988).

B. Cummings, ‘Print, Popularity, and the Book of Common Prayer’, in: E. Smith and A. Kesson (eds.), The Elizabethan Top Ten: Defining Print Popularity in Early Modern England (London/New York: Routledge, 2013), 135-144.

C. Dondi, Printed Books of Hours from Fifteenth-Century Italy: The Texts, the Books, and the Survival of a Long-Lasting Genre (Florence: Olschki, 2016).

S. Matter, ‘Transkulturelle Gärten. Zu den frühen Ausgaben des Hortulus animae, des Seelengärtleins und des Wurtzgartens’, in: I. Kasten and L. Auteri (eds.), Transkulturalität und Translation: Deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters im Europäischen Kontext (Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2017), 293-299.

M. Morrissey, ‘Sermons, Primers, and Prayerbooks’, in: J. Raymond (ed.), The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 491-509.