Glossary

Romance

Other languages

- Dutch: roman, prozaroman

- French: roman

- German: Roman, Prosaroman

- Italian: romanzo

- Polish: romans, powieść

- Spanish: novela, novela sentimental

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Narrative literature and historyDescription

In the history of English literature the word ‘romance’ is generally used for medieval and early modern long works of fiction in prose, typically “dealing with aristocratic personae and involving combat and/or love” (Finlayson 1995, p. 429). Pierre-Daniel Huet (1613-1721) wrote in his History of Romances: “I call them Fictions, to discriminate them from True Histories; and I add, of Love Adventures, because Love ought to be the Principal Subject of Romance. It is required to be in Prose by the Humour of the Times. It must be compos’d with Art and Elegance, lest it should appear to be a rude undigested Mass, without Order or Beauty.” (Huet 1715, p. 3-4).

The term ‘novel’ only gained ground in the second half of the 17th century, in England (novel) and Spain (novela), to set newly published narrative fiction apart from what were considered to be more traditional (chivalric) romances. In other countries, roman (French, Dutch), Roman (German) and romanzo (Italian) have remained current to this day to indicate long works of narrative fiction, whether or not love stories.

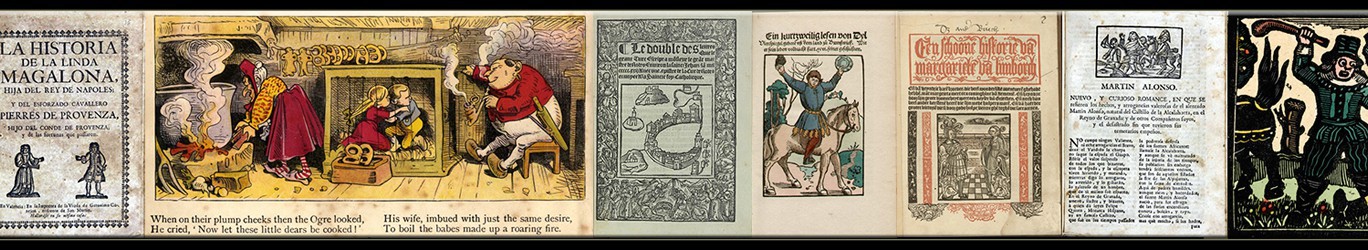

The German Prosaroman and Dutch prozaroman (in English also called prose romance) are modern terms used by researchers for fictional narratives in prose published in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries that targeted a broad reading public. Their prose form distinguishes them from medieval verse narratives about the same subjects. The texts themselves do not use this term; instead, they often carry the word history in their titles. Especially in the 15th and 16th centuries, these works were frequently illustrated with woodcuts that were reused or copied over and over again for subsequent editions.

Scholars of Spanish literature created the label novela sentimental (sentimental romance) for romances with a focus on love and emotions, even if they contained some chivalric action.

The Spanish term romance was used by contemporaries in a very different sense, to indicate texts – on a variety of subjects – in verse form: it “refers to the meter that has been most popular since medieval times, consisting of octosyllabic lines of verse with assonant rhymes in even lines.” (Botrel and Gomis 2019, 128).

Related terms

history, novel, sentimental romance, prose romance

Sources

M.H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms (Boston: Thomson, Wadsworth, 2005, 8th ed.).

J.-F. Botrel and J. Gomis, ‘“Literatura De Cordel” From A Transnational Perspective. New Horizons For An Old Field Of Study’, in: M. Rospocher, J. Salman and H. Salmi (eds.), Crossing Borders, Crossing Cultures. Popular Print in Europe (1450–1900) (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019), 127-142.

H.M.C.W. Blom, « Vieux romans » et « Grand Siècle » : éditions et réceptions de la littérature chevaleresque médiévale dans la France du XVIIe siècle, dissertation Utrecht University, https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/224190

M. Braun, ‘Illustration, Dekoration und das allmähliche Verschwinden der Bilder aus dem Roman (1471 – 1700)’, in: K.A.E. Enenkel, W. Neuber (eds.), Cognition and the Book: Typologies of Formal Organisation of Knowledge in the Printed Book of the Early Modern Period (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 369-408.

C. Demattè, ‘The Spanish Romances about Chivalry. A Renaissance Editorial Phenomenon on Which “The Sun Never Set”’, in: M. Rospocher, J. Salman and H. Salmi (eds.), Crossing Borders, Crossing Cultures. Popular Print in Europe (1450–1900) (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019), 217-226.

M.A. Doody, The True Story of the Novel (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996).

J. Finlayson, ‘Definitions of Middle English Romance’, in: S.H.A. Shepherd (ed.), Middle English Romances (New York: W.W. Norton, 1995), 428-456 (originally in The Chaucer Review 15 (1980-1981), 44-62, 168-181).

J.J. Gwara and M. Gerli (eds.), Studies on the Spanish Sentimental Romance, 1440-1550: Redefining a Genre (London/Rochester, NY: Tamesis, 1997).

P.-D. Huet, Traité de l’origine des romans (1670), transl. by S. Lewis (London: for J. Hooke and T. Caldecott, 1715).

A. King, The Faerie Queene and Middle English Romance: The Matter of Just Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), esp. Chapter 2: ‘Middle English Romance: Tradition, Genre, Manuscripts, and Prints’.

M. Menéndez Pelayo, Orígenes de la novela, 4 vols. (Madrid: Bailly-Baillière é hijos, 1905-1915).

J.-D. Müller, ‘Volksbuch / Prosaroman im 15./16. Jahrhundert. Perspektiven der Forschung‘, IASL Sonderheft 1: Forschungsreferate (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1985), 1-128.

M. Raimond, Le roman (Paris: Armand Colin, 2015, 3rd ed.).

J. Sánchez-Martí, ‘The Printed Popularization of the Iberian Books of Chivalry across Sixteenth-Century Europe’, in: M. Rospocher, J. Salman and H. Salmi (eds.), Crossing Borders, Crossing Cultures. Popular Print in Europe (1450–1900), (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019), 159-179.

R. Schlusemann, Schöne Historien. Niederländische Romane im deutschen Spätmittelalter und in

der frühen Neuzeit (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2016).

R. Schlusemann and K. Wierzbicka-Trwoga, ‘Narrative Fiction in Early Modern Europe. A Comparative Study of Genre Classifications’, Quaerendo 51 (2021), 160-188.

I. Watt, The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1957).

K. Whinnom, The Spanish Sentimental Romance, 1440–1550: A Critical Bibliography (London: Grant & Cutler, 1983).