Glossary

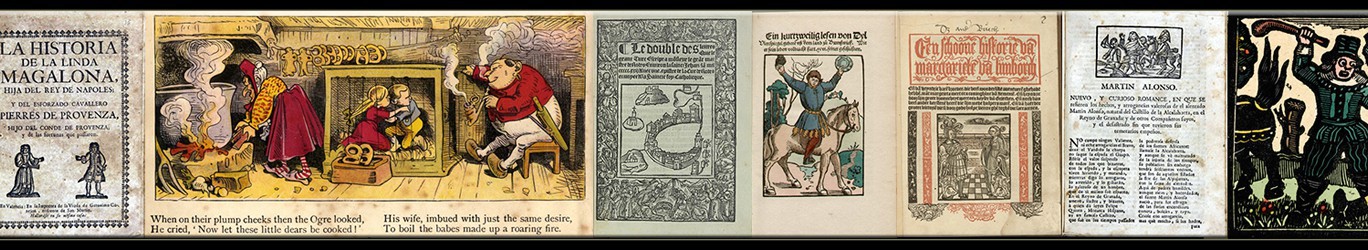

Book of secrets

Other languages

- Dutch: secretenboek, receptenboek, geheimenboek, kunstboek

- French: secrets, recueil de secrets, livre de secrets, recettes

- German: Rezeptbuch, Kunstbuch, Probirbuch

- Italian: libro di secreti/segreti, libro di ricette

- Polish: księga sekretów, sekret

- Spanish: recetario, secretos

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Knowledge and skillsDescription

Books of secrets or recipe books are ‘treatises that professed to reveal the “secrets of nature” to anyone who could read’ (Eamon 1994, 3). They tended to contain recipes and instructions to make medicines, recipes for preserving food (see also Cookbook), a great many cosmetic recipes, recipes pertaining to domestic management (see also Household manual) such as making inks and removing stains, and some ‘alchemical’ recipes, for refining chemicals.

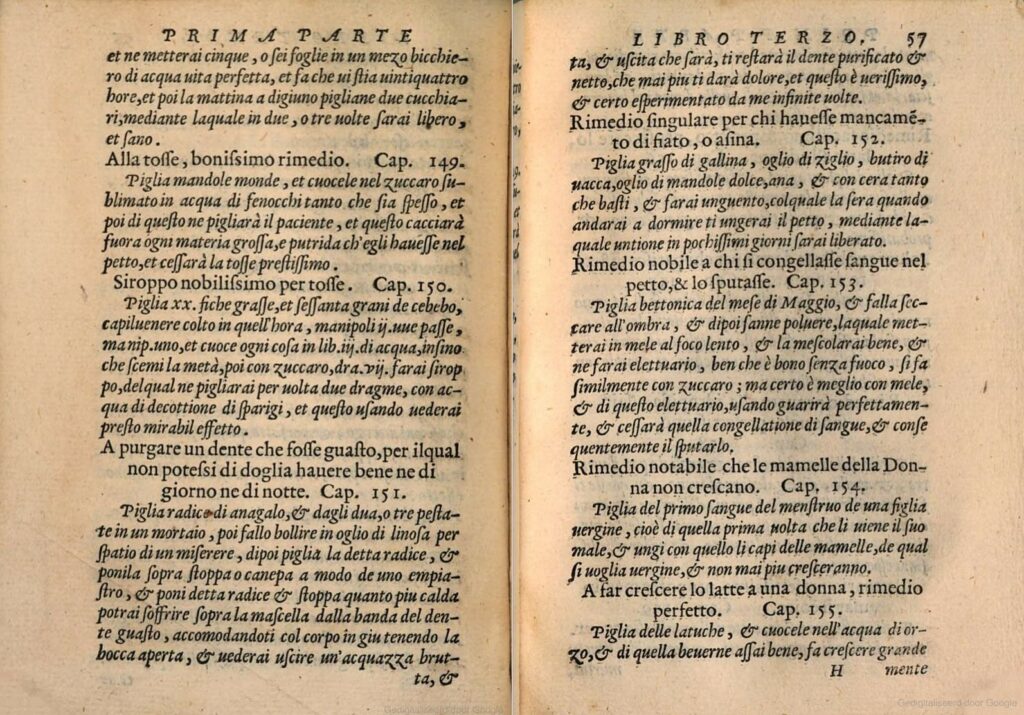

In Italy the words ‘recipe’ and ‘secret’ were used interchangeably as can be observed for example in the Secreti medicinali di m. Pietro Bairo da Turino, giá medico di Carlo secondo duca di Savoia (first ed. 1561), where the word ‘secrets’ in the title refers entirely to medicinal recipes. Some of the most famous and largest books of secrets were compiled by so-called ‘professors of secrets’ (poligrafi) in Italy. Many smaller, simpler, cheaper pamphlets were essentially anonymous, or in other words, compiled by an editor for the printer. One example is the Recettario Novo probatissimo a molte infirmita, e etiandio di molte gentilezze utile a chi le vora provare, 1532, Venice, printed by Zuan Maria Lirico. Full translations were rare and, as Geneviève Deblock’s study of the French renditions of the Italian Dificio di Ricette (2015) has demonstrated, these ‘translations’ often drew only marginally on the original text but heavily modified it with additions, deletions and substitutions, making it another text.

As a form of popular print, recipe books made their appearance in Italy already in the 15th century, such as the Thesaurus Pauperum (appeared in 1492 in vernacular) which was issued in 8o in 1497 and had another five editions up to 1548; of the Recetario de Galieno, first published in 1508, 39 subsequent editions were published in the 16th century, and seven in the 17th.

In the course of the 16th century, most other countries also established their own traditions within this genre. In England and the Low Countries, books of secrets made their first appearance around the 1520s.

Such books contained many seemingly simple recipes for herbal remedies and other medicines, but they required a lot of tacit and implicit knowledge. Commonly they opened with a table of recipes contained inside. After this, the structure of the book followed the body from head to toe, starting with maladies of the head and ending with sore legs and feet. Sometimes miscellaneous categories were added as well. The content and structure of the individual entries was not consistent, however. Some did not specify how to make the recipes described, while others did not specify the effects a recipe was supposed to have. The books also did not contain specific instructions on diagnosis, nor on how to prepare the ingredients.

Related terms

recipe book, how-to book, medical literature, pamphlet

Sources

L. Andries, ‘Les livres de secrets dans la littérature de colportage’, in: N. Jacques-Chaquin (ed.), Curiosité et libido sciendi XVIe-XVIIIe siècles (Cahiers de l’ENS de Fontenay-St Cloud, 1998).

S. Cavallo and T. Storey, Healthy Living in Late Renaissance Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

D. de Courcelles (ed.), D’un principe philosophique à un genre littéraire: les ‘secrets’. Actes du colloque de la Newberry Library de Chicago, 11-14 septembre 2002 (Paris: Champion, 2005).

G. Deblock, Le bâtiment des recettes: présentation et annotation de l’édition Jean Ruelle, 1560 (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2015).

M. DiMeo and S. Pennell (eds.), Reading and Writing Recipe Books 1550–1800 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013).

W. Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature. Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).

M. Fissell, ‘Popular Medical Writing’, in: J. Raymond (ed.), The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 417-430.

A. Kavey, Books of Secrets. Natural Philosophy in England, 1550–1600 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007).

D.L. Krohn, Food and Knowledge in Renaissance Italy. Bartolomeo Scappi´s Paper Kitchens (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

E. Leong, Recipes and Everyday Knowledge. Medicine, Science, and the Household in Early Modern England (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 2018).

E. Leong and A. Rankin (eds.), Secrets and Knowledge in Medicine and Science. 1500-1800 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011).

S. Laube (ed.), Material, Visual and Practical Dimensions of the How-to-Book in Early Modern Times (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming [2023]).

J. Martins, ‘The Afterlife of Italian Secrets: Translating Medical Recipes in Early Modern Europe’, in: M. Rospocher, J. Salman, H. Salmi (eds.), Crossing Borders, Crossing Cultures: Popular Print in Europe (1450–1900) (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019), 181-198.

J. Martins, ‘Les livres de secrets imprimés et traduits en Europe: la circulation des secrets italiens entre 1555 et 1650’, Encyclo. Revue de l’école doctorale Sciences des Sociétés ED 624 7 (2015), 145-164.

https://hal.science/hal-01479928 (accessed 3 April 2023).

S. Minuzzi, ‘“Quick to say Quack”. Medicinal Secrets from the Household to the Apothecary’s Shop in Eighteenth-century Venice’, Social History of Medicine 32:1 (2019), 1-33.

S. Minuzzi, Sul filo dei segreti. Farmacopea, libri e pratiche terapeutiche a Venezia in età moderna (Milan: Unicopli, 2016).

E. Renzetti and R. Taiani (eds.), Provato e certo: rimedi secreti tra scienza e tradizione (Trent: Fondazione Museo Storico del Trentino, 2008).

Additional information was provided by Sandra Cavallo, Tessa Storey and Sabrina Minuzzi.