Glossary

Medical literature

Other languages

- Dutch: medische literatuur

- French: livre de médecine, livre de santé

- German: Medizinalliteratur, heilkundliche Literatur

- Italian: libro di medicina, letteratura medica

- Polish: literatura medyczna

- Spanish: libro de medicina

Material form

Printed bookSubject

Knowledge and skillsDescription

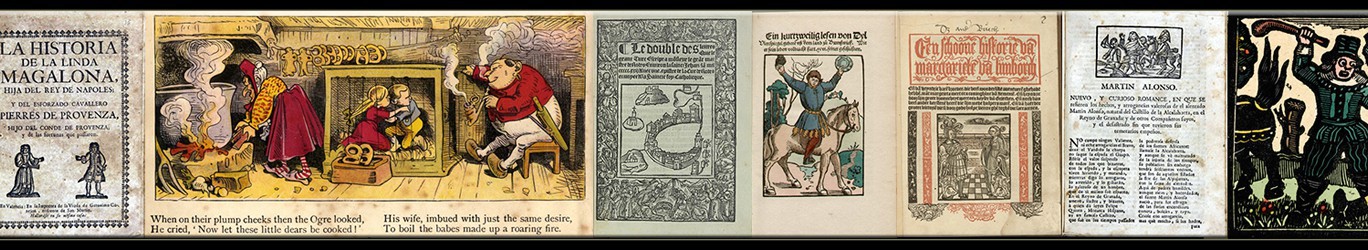

An increasingly vast range of vernacular medical literature flowed from the printing presses across Europe since the late fifteenth century. Categorisation is difficult because text types overlapped and merged in many ways (e.g. theoretical explanations and practical remedies, preventive and curative medicine), and many kinds of compilations of medical knowledge appeared.

Some works were decidedly more specialised, and in that sense less ‘popular’, than others. Herbals and surgery manuals, for example, often appeared as large, illustrated (and therefore expensive) folios, but in many cases smaller and cheaper versions quickly followed suit.

In the highly variegated and competitive early modern ‘medical marketplace’, medical books served practitioners with different levels of medical expertise and literacy, including (novice) barbers and surgeons, pharmacists, midwives, and charlatans. University-trained physicians were at the most specialised end of the spectrum. At the same time, many households and religious houses also possessed medical books to be able to take care of their own health to some degree. Almanacs often also included medical instruction, for example on letting blood or in the form of a regimen. Regimens were especially often intended as do-it-yourself healthcare, aimed at preventing rather than curing ailments. Some books of secrets were entirely devoted to medicinal recipes.

Tracts about epidemic diseases appeared especially at times of outbreaks. By far the most of these were plague tracts, but other diseases such as syphilis (the ‘French disease’) were also discussed in separate publications.

Related terms

how-to book, materia medica, remedies, anatomy, surgery, herbal, plague literature, regimen, recipe book

Sources

J. Arrizabalaga, The Articella in the Early Press, c. 1476-1534 (Cambridge/Barcelona: Cambridge Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine, 1998).

L. Brockliss, C. Jones, The Medical World of Early Modern France (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).

A. Carlino, Paper Bodies: A Catalogue of Anatomical Fugitive Sheets, 1538-1687 (London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1999).

A. Carlino, La fabbrica del corpo. Libri e dissezione nel Rinascimento (Turin: Einaudi, 1994).

A. Cunningham and O.P. Grell, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Religion, War, Famine, and Death in Reformation Europe (Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

M. Fissell, ‘Popular Medical Writing’, in: J. Raymond (ed.), The Oxford History of Popular Print Culture, Vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 417-430.

D. Gentilcore, Medical charlatanism in Early Modern Italy (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

L. Hill Curth, English Almanacs, Astrology and Popular Medicine: 1550-1700 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007).

M. Laget, ‘Les livrets de santé pour les pauvres aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles’, Histoire, économie et société 3:4 (1984), special issue on ‘Santé, médecine et politiques de santé’, 567-582.

S. Minuzzi (ed.), special issue ‘Printing Medical Knowledge: Vernacular Genres, Reception and Dissemination’, Nuncius 36:2 (2021).

R. Myers, M. Harris (eds.), Medicine, Mortality, and the Book Trade (New Castle (Delaware): Oak Knoll Press, 1998).

M. Nicoud, ‘Chapitre X. Le livre diététique: manuscrits et imprimés’, in: Les régimes de santé au Moyen Âge: Naissance et diffusion d’une écriture médicale en Italie et en France (XIIIe- XVe siècle) (Rome: Publications de l’École française de Rome, 2007).

V. Nutton, Renaissance Medicine. A Short History of European Medicine in the Sixteenth Century (Abingdon, Oxon, New York: Routledge, 2022).

M. Ramsey, Professional and popular medicine in France, 1770-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

R. Rey, ‘La vulgarisation médicale au XVIIIe siècle: Le cas des dictionnaires portatifs de santé’, Revue d’histoire des sciences 44:3-4 (1991), 413-433.

P. Slack, ‘Mirrors of Health and Treasures of Poor Men: The Uses of the Vernacular Medical Literature of Tudor England’, in: C. Webster (ed.), Health, Medicine and Mortality in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1979), 237-273.

M. Stolberg, Learned Physicians and Everyday Medical Practice in the Renaissance (Munich/Vienna: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2021).

J. Telle, Pharmazie und der gemeine Mann: Hausarznei und Apotheke in der frühen Neuzeit : erläutert anhand deutscher Fachschriften der Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel und pharmazeutischer Geräte des Deutschen Apotheken-Museums Heidelberg (Weinheim: VCH, 1988).

T. Taape, ‘Common Medicine for the Common Man: Picturing the “Striped Layman” in Early Vernacular Print’, Renaissance Quarterly 74 (2021), 1-58.

C. Verry-Jolivet, ‘Les livres de médecine des pauvres aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. Les débuts de la vulgarisation médicale’, in F.-O. Touati (ed.), Maladies, médecines et sociétés, L’Harmattan et Histoire au présent, 1993, t. I, p. 51-61.

A. Wear, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000)